More Stories

All month long for Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, mental health advocates have been highlighting ways people can help those who may be dealing with depression or thoughts of suicide.

The mental health care crisis appears to be growing, especially among school children. Suicide is now the second-leading cause of death for teenagers, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Team 12 Investigates concerns that services are hard to find for children and teens who are struggling with their mental health.

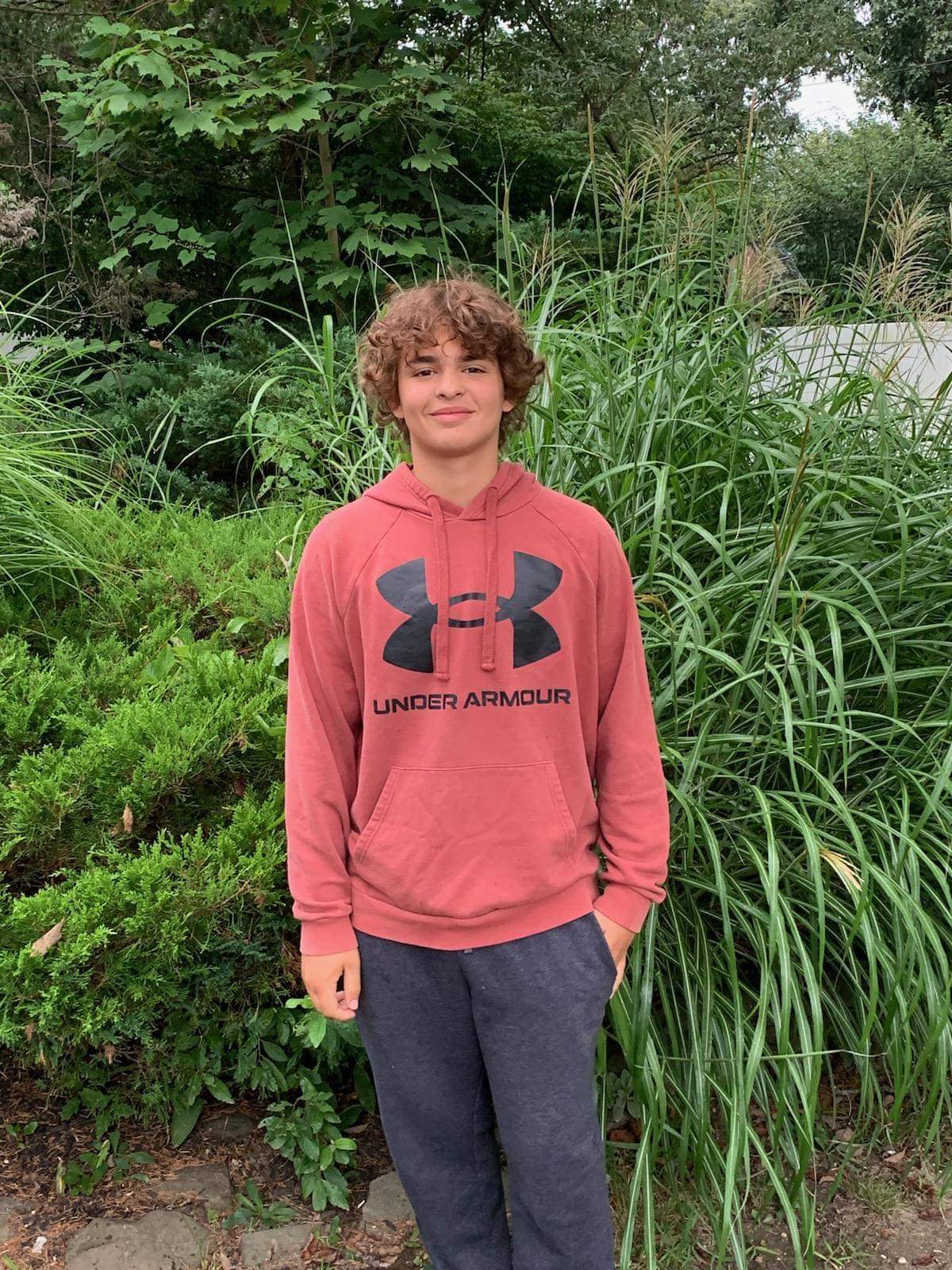

One year ago, Chris Coluccio’s 14-year-old son died by suicide suddenly and unexpectedly. The unimaginable loss came as a shock to his family.

“I don’t know anything more dark than a child committing suicide,” said Coluccio.

Coluccio wishes he knew the signs to look for and how to intervene. Thinking back to what he may have missed, he realized mental health was rarely a topic at his son’s school.

“Out of all the conversations I've ever had about Christopher, with his guidance counselors and his teachers, nothing about his mental wellness was ever something that we really discussed,” said Coluccio.

Within months of Christopher’s death, Coluccio said there were at least two other teenage suicide deaths in the community. The grief drove him to create a nonprofit in memory of his son to educate the community and help raise awareness of mental health among teens.

“There needs to be a lot more of this forward-looking, positive outlook, life coach modeling to really show kids that this is just a moment in time,” said Coluccio.

Through the Christopher A. Coluccio Foundation, Coluccio works to end the stigma surrounding conversations about suicide prevention. He said asking your children if they are having thoughts of suicide does not put the idea in their heads—rather it can help them come out of dark places.

However, mental health resources are scarce in many communities.

After a student died by suicide in 2013, East Hampton School District worked with elected officials to create more crisis response services on the East End. They partnered with Family Service League to provide a mental health clinic, but the pandemic created a backlog never seen before.

“I’ve never in my career, in over 20 years as an administrator, ever seen this much demand for mental health,” said Adam Fine, superintendent of the East Hampton School District. “There are other obstacles that prevent people from being social workers and psychologists on the East End. The cost of living being one. Traffic being another. So, we have a wait-and-see mentality with that, but we do have the supports to address it in the school.”

School district officials said attendance significantly dropped last school year. It was the first year since the pandemic that students fully returned to classrooms, albeit with masks and other COVID-19 safety precautions, and many teenagers struggled with that adjustment.

“Not only more students not making it into the building, but for longer periods of time,” said Ralph Naglieri, assistant principal at East Hampton High School. “We saw a huge increase in anxiety issues to the point where we were doing our best to send our support staff, our social workers, to houses to encourage students to try to come in.”

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 78% of New York communities do not have enough mental health care providers to serve families.

Team 12 Investigates the problem across Long Island. We asked more than 30 agencies that deliver mental health care whether they are seeing a shortage of providers and why. Though they did not provide specific data, some centers said they are losing staff to emerging telehealth companies. Others admitted they cannot offer higher salaries that workers are demanding.

Employers also said providers are leaving the field because it is too stressful. They also say some providers are leaving Long Island because it is too expensive. As a result, they said it is taking months to find qualified workers and some positions have stayed open for over a year.

Mental health advocates are turning to schools to fill the void.

Ann Morrison-Pacella, the Long Island area director of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, is hoping to launch a new mental health initiative in schools for grades K-5. The nonprofit received a grant to introduce a children’s book, titled "Gizmo’s Pawesome Guide to Mental Health," into dozens of classrooms for free this fall. The message of mental health and wellness is told by a therapy dog named Gizmo.

Unfortunately, getting mental health programs into classrooms has not always been easy. Many school districts previously turned away help. Morrison-Pacella said she is sensing a change.

“I don’t think it was that schools didn't want to do it. It just wasn't a priority with all the other things that they had to fit into the school day and their curriculum,” explained Morrison-Pacella. “Now, they're understanding that they need to fit this in as one of the priorities.”

The solution to finding additional mental health services for children and teens does not rest solely with schools. Coluccio believes public libraries could be great locations to place a wellness counselor.

His nonprofit is also a resource for communities, holding events to help start communications about mental health between parents and children. It has proven to be the light for those who may be in dark places, providing the same support Chris’ family received after their insurmountable loss.

“The day after Christopher died, we had a hundred people in our driveway that were doing stuff for us,” Coluccio explained. “Mowing our lawn, supporting us, putting flowers out there, giving us hugs so if we can do that back for them, that’s huge.”

Some states have passed laws that allow students to take mental health days. New York lawmakers considered a similar bill two years ago, but it never made it out of the Senate Education Committee. The bill would have to be reintroduced by its sponsor in January before it can be considered again.

If you or someone you know is struggling with depression or thoughts of suicide, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is available 24 hours. Call or text 988 or chat with someone at 988lifeline.org.

More from News 12

2:05

City officials prepare for NYE celebrations in Times Square

0:41

Mamdani appoints Kamar Samuels as chancellor of NYC Public Schools

1:52

‘Not a rookie job.’ ATM theft duo behind citywide spree targets East New York

1:37

Light snow expected on New Year’s Eve in Brooklyn

1:49

15-year-old boy shot in the head at Crown Heights apartment building

0:38